Street tales from Myanmar: ‘Take care of our baby if I die’

Every day, ordinary people in Myanmar are making difficult choices in the face of an increasingly violent response to their mass protests.

The protesters want a return to their democratically-elected civilian government, after the military seized control on 1 February claiming there was widespread fraud in last year’s election.

According to the UN, at least 149 people have died during the civil disobedience since 1 February – though the actual figure is thought to be much higher.

Here are the stories of those who continue to come out onto the streets, told in their own words.

The woman fighting for her daughter’s future

Naw is the leader of the General Strike Committee of Nationalities. She says she’s participating in the strikes for the sake of her one-year-old daughter, whom she hopes can have a better future.

I am a member of [an ethnic minority group in Myanmar] called the Karen so protesting is not new to me.

Today’s protesters demand the release of State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint and the verification of the 2020 election result.

But we, the ethnic minorities, have deeper demands. Our vision is to establish a federal democratic union with all nationalities who belong in Myanmar.

The military ruled with the divide and conquer strategy for many years, but now all nationalities have become united.

I have a little girl. She’s one.

I don’t want her to suffer from my actions. I got involved in the protest for my daughter because I don’t want her to grow up under a dictatorship like I did.

Before I joined the protest, I discussed it with my husband.

I asked him to take care of our baby and move on with life if I get arrested or die in this movement.

We will finish this revolution on our own and not hand it over to our children.

The medical officer helping doctors flee

Nanda* works for a hospital in the town of Myeik. Medical workers have been at the forefront of the protests in Myanmar, but Nanda says those in Myeik have had to go into hiding for fear of being taken by military

It is the night of 7 March, before curfew hours kick in.

I am driving a car with tinted windows – I pick up an orthopaedic surgeon, his wife, a physician and his family among others – and under the cover of darkness, we pack their bags into our car, and drive them to a safe house.

Just a day ago, government officials called hospitals in Myeik to ask for names of specialists, medical officers, and nurses that participated in the Civil Disobedience Movement.

There’s fear among [us] – why do they want their names? What might happen to them if they are called in by officials?

All the in-service doctors – those working for the government – decide they will go into hiding, for fear of what might happen if they are caught. I have been assigned to help some of the doctors escape.

Back in our car, the atmosphere is one of disbelief and disgust.

“Why are people like us [doctors and medical staff] having to hide like criminals while they do as they please?” asks the physician.

I feel sick in my stomach. I never imagined I would one day have to hide [doctors] for doing nothing wrong.

Starting tomorrow, the people of Myeik will only have a few specialists to take care of them.

There will not be enough surgeons to fix the broken fingers, hands, and skulls of protesters and bystanders whom the [military officials] beat.

There will be zero obstetricians and gynaecologists to help women give birth in Myeik.

Medical workers have been an important and essential part of this movement, but now they are gone.

The man behind the camera

Maung is a filmmaker in Yangon. When protests started, he decided he would document each day in an effort to show how the movement evolves.

It was an unforgettable day – 28 February. I was at the frontline on Bargaya Street [in Yangon], standing behind the barricades.

I was filming with my phone. Hundreds of protesters shouted slogans and banged bottles and cans.

About 100 people marched towards us quickly – I don’t know whether they were police or soldiers.

Without warning, they started shooting at us with sound bombs, bullets and gas bombs.

I ran into a street where I had already scouted for an escape route while trying to continue filming. Most of us managed to escape.

When I go to the protests now, I have to bring a helmet and heat-resistant gloves.

We try to throw back the tear gas canisters when given a chance. Most of the time, to diffuse the gas canisters, we just cover it with wet clothes and pour water on it.

Many wear cheap gas masks which cannot fully protect them against the effects of gas. We found out [the drink] Coke is most effective to wash off the gas from our face.

As a filmmaker and a protester, I decided to protest and to make a very short film everyday.

Now looking back at the videos, I can re-experience how the resistance has changed – from peaceful protests to the [ones] where we are risking our lives.

This is more surreal than any film.

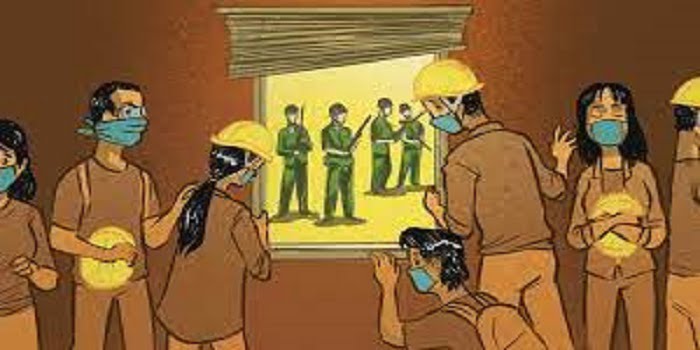

A woman trapped by military forces

Phyo* is a researcher who was one of 200 people attending a protest in Sanchaung, a district in the city of Yangon, when they found themselves cornered by military officials who prevented them from leaving. At least 40 people were arrested.

It was 8 March, around 2pm, when the security forces came [and trapped us].

We began seeing house owners opening their doors and waving their hands, [beckoning] us into their homes.

The security forces were outside, waiting for us to come out. There were seven of us in our house – six women and one man.

The hosts were very kind and offered us food. We thought it would be fine to leave a few hours later [but] around 6:30pm, we started to get anxious.

We realise they [security forces] were not going to leave. We decided to make plans [to escape].

Our hosts told us which streets were safe to hide in, and which other places offered hiding spaces.

We left all our belongings at the first host’s house. I changed to a sarong [a piece of cloth used traditionally as a skirt] so I would look more like a local resident- and left the house.

I also uninstalled many apps on my phone and took some spare cash.

We spent the entire night at another safe place. By morning, we heard the security forces were not there anymore.

*Names have been changed for safety and interviews have been edited for clarity.

Source: BBC