Bangladesh fears a coronavirus crisis as case numbers rise

As hospitals in Bangladesh turn patients away, and frontline workers bear the brunt of rising case numbers, there are fears the densely populated South Asian country could become a new global hotspot.

For years, Vernon Anthony Paul served in the Pakistan air force. He fought in the Bangladesh war of independence in 1971 and was held as a prisoner of war.

The 75 year old died on a Wednesday evening in May 2020, when the coronavirus isolation unit he was being treated at in Dhaka burnt to the ground.

“He used to tell stories of how they dug their own trenches during the war. Even the bombs couldn’t kill my dad,” said his son, Andre Dominic Paul. “But the carelessness of our own people in Bangladesh killed my father.”

In the days before his death, Vernon Anthony Paul reported severe breathing problems but tested negative for Covid-19. It’s thought he had pneumonia. He was turned away from the ICU unit of a hospital because it was full.

His family took him to the private United Hospital in the city, but were told he couldn’t be admitted to the ICU unless he was tested again by them, to be sure he didn’t have Covid-19. Stigma and fear around the virus has seen some patients in Bangladesh denied proper treatment.

Andre said his father was offered a bed in the makeshift coronavirus isolation unit, built on a badminton court in the hospital grounds, until his test results came. “We tried to say, why would you put him there with other Covid patients?” his son recalled.

In the end, Andre decided to admit his father because he had no other option. He said he was asked to agree that if Vernon caught the virus while there the hospital would not be responsible. It was a decision he would regret forever, he said.

Andre was standing in the hospital car park when he first saw sparks fly from an air conditioning unit. “It was all smoke, black thick smoke, and it was hard to breathe,” he said. “The one thing on my mind was that my dad was getting burned inside.”

All five patients in the unit died in the fire. A police investigation found the structure was unsafe and had been built using flammable materials. Hand sanitisers and oxygen canisters which were stored inside added to the risk, and the unit had just one fire exit and insufficient fire extinguishers.

Shudip Chakroborty a deputy police commissioner who led the inquiry, told the BBC that the private hospital had failed to take proper precautions. The hospital denies negligence.

The tragedy was a reminder of Bangladesh’s poor record on fire safety and the challenges the nation faces with an already under-resourced healthcare system. Less than 3% of Bangladesh’s GDP is spent on healthcare, compared with about 9.7% in the UK.

The country has one of the lowest ratios of hospital beds to patients in the world. There has been a shortage of ICU beds during the coronavirus outbreak – figures vary but it is estimated that there are just over 1,000 beds for a population of more than 160 million.

And with limited beds, stories of patients being turned away from hospitals continue to emerge. Dr Moyeen Uddin tested positive for the virus at the end of March, but was unable to get onto a ventilator at the very hospital he worked at, in his home city Syhlet.

“At that time there were no ventilators dedicated to Covid patients,” said Salahuddin Ahmed, another doctor who had been friends with the doctor for decades.

Dr Uddin was transferred to a hospital in Dhaka, more than 200 km away, but he later died, leaving behind a wife and two young children.

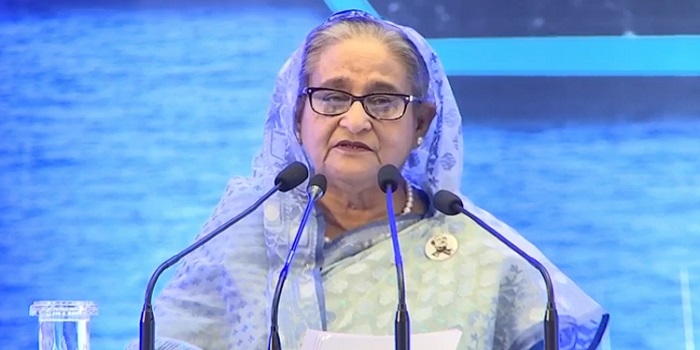

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was among those to offer condolences. “This noble-hearted physician gave treatment to the people taking risk of his own life,” she said.

There was anger on social media that his own hospital had not treated him. A spokesman told a newspaper in Dhaka that the hospital was a general hospital which lacked facilities to treat Covid patients.

Mr Ahmed, a leading epidemiologist in Dhaka who works for Johns Hopkins and Edinburgh universities, said his friend’s death illustrated the need to increase hospital capacity and train more medical staff as case numbers rise.

“He was in the middle of his career and we lost him. It was a huge impact for all of us,” he said

At least 34 doctors have died of Covid-19 in Bangladesh, and as many as 1,180 have reportedly been infected.

And cases are now rising sharply among the general population after a nationwide lockdown was lifted. The first cases were confirmed in the country on 8 March, and lockdown began on 26 March – three days after the UK.

“I think we missed an opportunity,” said Dr Romen Raihan, a public health expert in Bangladesh. “I think the so-called lockdown didn’t work properly.”

Dr Raihan said that as time progressed, exemptions were made to the lockdown, with thousands of garment workers allowed back to work to fulfil orders for Western brands, and places of worship reopening.

In April, more than 100,000 people took to the streets to attend the funeral of Maulana Jubayer Ahmed Ansari, a popular member of Bangladesh’s Islamist party. And facing economic hardship, thousands of migrants travelled home to their villages.

As in many nations, frontline workers have born the brunt. More than 7,000 police officers have contracted the virus, at least 1,850 of them in the capital city Dhaka, the most densely populated in the world. As well as maintaining curfews, police officers have been disinfecting streets, distributing food and relief, and escorting people to hospital, in some cases with inadequate PPE.

As Bangladesh opens up, frontline workers will continue to be affected, but there are fears the virus will sweep the population at large. Some areas with high numbers of cases are being contained to control the spread, but with a healthcare system already bursting at the seams, Bangladesh could slide into a crisis it cannot control.

According to Dr Raihan, containing the virus is the only hope. “A curative approach is suicidal in Bangladesh,” he said. “Our health system is not prepared.”

Source:BBC